Whether or not we are in a revolutionary period of history is open to interpretation. I’m sure that there are plenty of compelling arguments against this theory; further, I’m not a historian: I primarily read fiction, and when I read–or more likely listen to–a non-fiction text on history, I’m mostly doing so in order to better understand art and literature–I’m not paying close attention to details about economics and technology and so on. For instance, two years ago I listened to a book on the French Revolution from Will and Ariel Durant’s Story of Civilization series, entitled Rousseau and Revolution: A History of Civilization in France, England, and Germany from 1756, and in the Remainder of Europe from 1715, to 1789. Naturally, a book like this covers a lot of ground, but roughly at its center it was about the contrast between Voltaire and Rousseau, who are kind of intellectual poles within modernity. Voltaire, an enormously famous intellectual during the 18th century, was basically staking a claim for the self against the strictures of Catholicism: he is enlightenment: pro-civilization and progress, pro-free speech, and pro-aristocracy; Rousseau, who was incomparably less influential, is a kind of foil for Voltaire: he views civilization as corrupting and envisions man as best adjusted to a kind of idyllic state of nature. He thinks school is the source of this corruption and that people–especially children–should spend time outside, that indigenous peoples live as God intended, and so on. In a way, these two names become associated with old impulses: Voltaire represents a kind of Apolonian rationality; Rousseau represents Dionysian irrationality, and as the modern period, roughly beginning in the 18th century, progresses, these two impulses– Voltaire’s Enlightenment and Rousseau’s Romanticism–clash in the forms of Communism and Fascism: these are two major poles within modern Western thought; they are the respective sides in the ongoing sometimes hot, sometimes cold civil and cultural war.

At some point, I read part of Aleksandr Dugin’s Fourth Political Theory and found his method of comparative philosophy useful, even if his political ideas are different from my own. In my own political thinking and based on my limited and inexpert reading of Dugin, I found myself comparing and contrasting what I think are the four primary philosophical tendencies of modern Western history: Communism, Fascism, Liberalism, and Religious Traditionalism (overtly Catholic and Islamic states). In order to understand these complex ideas, I had to reduce them to simpler ideas. So far, my model, which I think works pretty well, is the following.

Communism derives its authority from the intellect.

Fascism derives its authority from instinct.

Liberalism derives its authority from self-determination.

Religious traditionalism derives its authority from the conscience.

The reason that this model of reduction is helpful is because as the complex, historical constructs built around, say, Communism collapse, you might believe its underlying impulse has also collapsed–but you would be wrong. That same materialist vision Marx derived from Feuerbach thrives in capitalist America–in the minds and hearts of ultra-capitalists Elon Musk and Marc Andreesen, for instance. This isn’t a contradiction: those who put their faith in disembodied intellect have learned from the past: it once appeared that the command economy would best serve the reign of materialist reason; now, it appears that capitalism does.

Once we understand the sources of ultimate authority for each of these philosophies, we can consider associated aesthetics. The tradition associated with materialist rationalism orients towards material good because, in this worldview, there is nothing beyond the material world: there’s no soul; there’s no afterlife; there’s no God: just physics. With this orientation in mind, it’s not too surprising that communist theorists identified a problem with the so-called “aura” contained in original works of art: a work of art’s sense of uniqueness and originality. Aura can be connected to context: think of the experience of viewing a hand painted icon in a silent room within a seminary.

This is a ChatGPT generated image, but it helps you grasp the concept: aura is derived from both the physical context of the wall, the room, the streaming sunlight, the reverent religious atmosphere and the knowledge that the icon is a one-of-one original. That aura is an uncomfortable concept for rationalists is probably obvious, but I want to quote Walter Benjamin on this subject so we can understand the rationalist program for the arts.

It would therefore be wrong to underestimate the value of [theses about how art should be produced and reproduced] as a weapon. They brush aside a number of outmoded concepts, such as creativity and genius, eternal value and mystery—concepts whose uncontrolled (and at present almost uncontrollable) application would lead to a processing of data in the Fascist sense. The concepts which are introduced into the theory of art in what follows differ from the more familiar terms in that they are completely useless for the purposes of Fascism. They are, on the other hand, useful for the formulation of revolutionary demands in the politics of art.

Look at his conception of the onramp to Fascism: “outmoded concepts, such as creativity and genius, eternal value and mystery”; look at the conflation of concepts associated with Greenwich Village bohemians (“creativity and genius”) and those associated with Christianity and other religions (“eternal value and mystery”). In the rationalist framework, there isn’t a significant difference between some airport bookstore prattle about creativity and the Catholic Church’s entire corpus systematizing eternal values: both of these projects reduce to immaterial vapor. Further, it’s easy to see how “aura” sits uncomfortably among these other fascist concepts: it isn’t material; it isn’t political. Therefore, the project must be to develop an artistic framework in which these immaterial concepts–like creativity, genius, eternal values, mystery, and aura–are excluded. To do so will be “democratic.”

How to do this? Benjamin argues that mechanical reproduction “always depreciates” the “quality of [an art object’s] presence”; therefore, communists should emphasize mechanically reproducible forms–like photography, film, recorded music, and so on–in order to promote art experiences in which there can be no aura. Additionally, mechanical reproduction disconnects aesthetic experience from the private, often sacred sphere, and as the ritualistic–or religious–aesthetic foundation evaporates, another appears: mass politics. So, when anti-woke Liberals refer to woke political commitments as “a religion,” necessarily a pejorative, or when you hear people decry the replacement of politics with religion, they should understand that this was explicitly the materialist program: Marxist, yes, but also Liberal. Therefore, both Communist and Liberal art, which we should understand as art whose function is to glorify the cult of reason, will be both mechanically reproducible in mass quantities and concerned with mass politics. Today, the sources of mechanically reproducible art are the twin power centers of capitalist Liberalism: Hollywood and Silicon Valley, where a capitalist variant of Marxist rationalism reigns in the minds of investors.

I’m sure my leftist friends would disagree with me, but this is one of the important assumptions that I think a lot of rightwingers share: we live in a country whose culture is roughly materialist–either historical or economic–even though the economy happens to be free. This inherent materialist orientation of the culture is different from and in addition to the ludicrous cultural marxism phenomenon.

The fascist counterclaim–which I wouldn’t characterize as “reaction”–was probably best expressed in The Futurist Manifesto, written in 1909 by Italian Fascist poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. It is different fundamentally from the communist program. The platform is whimsical and violent, valorizing “danger…and rashness,” “movements of aggression, feverish sleeplessness, the double march, the perilous leap, the slap and the blow with the fist.” See how these objectives are different from the kind of soulless endeavor of politicizing and secularizing artwork. There is an embrace of unreason (“danger,” “rashness,” “aggression,” etc.); there is a sense of mania and mission (“sleeplessness,” “the double march,” etc.) The language is much more visual and frankly interesting, too: “We will sing of the great crowds agitated by work, pleasure and revolt; the multi-colored and polyphonic surf of revolutions in modern capitals…factories suspended from the clouds by the thread of their smoke…” The idea that fascists were goose-stepping drones seems incorrect in this light: Marinetti, at least, was a wild-eyed romantic, and in this light we understand communist aversion to words like “creative” and “genius” because it appeals to personalities like this. There is, in my mind, a bright line between Tommaso Marinetti (or Gabriele D'Annunzio) and Kanye West. It’s important to understand that the fascist orientation–a kind of restless seeking of war and adventure–is also, in my view, not great. Still, it is colorful and spectacular and fantastical; in contrast, the communist vision is just so inhuman and mechanical.

With all of this prologue in mind, we can begin to consider

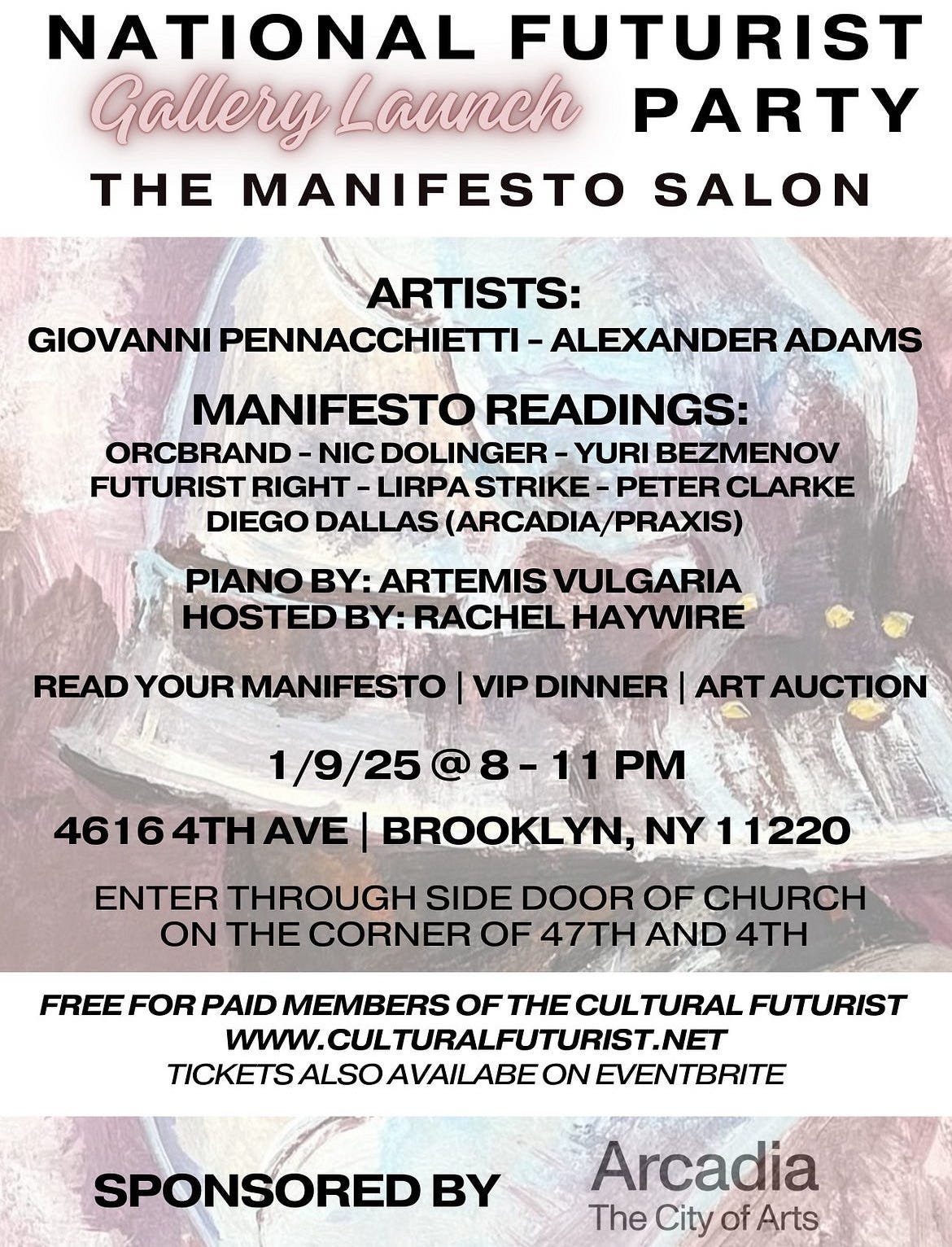

’s National Futurist Gallery launch party–also called “a manifesto salon.” Right from the beginning, there are important words to consider, especially “National,” “Futurist,” “manifesto,” and “salon.” Marinetti’s futurism is clearly the inspiration, but she added “National” to the title to make things explicit: this is an American Nationalist-Futurist art project; this is a “salon,” presumably in 18th century French sense, open to revolutionary ideas opposed to the dominant American cultural program.Haywire got access to a Methodist Church serving an apparently Chinese-American community. The 4th Avenue Methodist Church on 4th Avenue in Sunset Park, Brooklyn looks like this:

Outside the side door on the left part of the photo (by the daycare sign), there were two security guards checking for tickets. I showed them the eventbrite ticket on my phone, and both actually scrutinized it for a few seconds, confirming that the text was correct. As a former soldier who did entry control point work, I was impressed with this degree of competence. I stepped inside and saw an open event space room, which was really probably the church’s foyer. Let’s say the room was 50’ x 50’. At the far wall opposite the doorway I was standing in, there was a wooden platform that was probably 15’ deep and 30’ wide. On that platform, there were folding chairs and maybe 10-15 seated people looking in the direction of the door I was standing in. The lights were out, but there were rotating patterns of light on the walls and ceiling of the cavernous room. Before the silent audience, Rachel Haywire was skipping and twirling to music in the dark.

I was impressed by her willingness to go for it; I also understood immediately that this would not be a night of following the flow of logic line by line in a series of rightwing manifestos lamenting immigration or feminism. The modes of communication in the first seconds of the event were movement and color and atmosphere and vibe, roughly reducible to aura. Part of the aura of this scene is the context. I can imagine someone rolling his eyes: a bunch of adult children in Brooklyn frittering away time and resources on a Quixotic art project. But as a married dad with a stable career, a mortgage, a suburban church, a bourgeois life, I disagree. If this scene had been at Comicon and Haywire were performing in a Bat Girl costume, I’d agree; if it were at a communal home of Bay Area rationalists and the seated attendees were in furry outfits, I’d agree. But this was a room of Rightists and Catholics and Futurists gathering in New York City to take new ground in the general culture war for the arts in general. On this same night, for instance, and at this same time, there was a much larger event in Manhattan at which Anna and Dasha interviewed Dean Kissick about his Harper’s article supporting the claim that American arts had aligned with “the dominant social-justice discourses of the day, with works dressed up as protest and contextualized according to decolonial or queer theory, driven by a singular focus on identity.” That event was probably much better attended than Haywire’s for two reasons: (1.) the star power of Harper’s, Anna and Dasha, and Kissick, but also (2.) talking about the ways that “wokeness has gone too far” is popular among passive consumers of culture: there’s a big audience for it. The more interesting question is, What’s the solution? Because the Futurist program is a philosophical balance against the soulless Marxist program, I think that a National-Futurist art gallery in Chelsea, which is Haywire’s plan, should be part of the answer.

One had to cross the dance floor in order to get a seat, and I did so quickly, feeling like I had to avoid Haywire, who was in a kind of flow state. I sat and recognized others from various Sovereign House events, but at that point–right around 8:00 PM, the advertised start time–there were only a few people present. I was impressed with the height of the room: it had a tall, two-story ceiling, and there was a wrap-around balcony and a number of large windows. I saw patterns of light moving against the glass and walls and balcony. Soon, Haywire was at the command center–a folding table supporting the projector and her laptop–opening a Zoom meeting projected onto the windows and wall above the balcony. The face of Giovanni Pennacchietti looked down on the assembled audience.

I knew him as Gio’s Content Minded Corner on X, though I didn’t know that he was an artist. I remember thinking he gave a literate talk about Italian Futurists and about his own work as an artist on the internet; he spoke–in a kind of chipper and innocent way–about Marinetti and another painter, whose name now escapes my memory, and as he spoke my visual attention occasionally drifted to the door, where newly arrived attendees appeared as silhouettes. Some lingered in the doorway; others crossed and found seats on the wooden platform. Soon, the chairs around me were filled, and I remember feeling glad that people were interested.

There were a few connectivity issues with Zoom, and at one point the meeting abruptly ended, which elicited some chatty commentary from the sympathetic and unfazed audience. Gio appeared again and asked for questions. I asked him to speak on the subject of poptimism in music, which he did capably, relating that phenomenon to the larger tidal cycle of incoming and outgoing vibes.

Haywire thanked Gio and transitioned to the next stage of the event: manifesto reading. The lights went on, and Orcbrand, a chaotic poster, who apparently just published his own home address on X to win $100 and instead was locked out of his account for doxxing, crossed the balcony. He was a heavyset, bearded guy bundled in a winter jacket and hat. He stood at the lectern and in a fit of pique explained that he had lost the transcript of his manifesto, nor could he find it on his phone. Haywire asked if

would speak in his place, and Orcbrand shouted a few expletives as Nic ascended and approached the lectern. My attention shifted; I was interested in the flow of logic in his address, which was an impassioned and well-reasoned exhortation in support of annexing Greenland from the Danes. Orcbrand then stood at the lectern and delivered at last his speech in almost a fit of rage. I don’t remember the details, but I do remember being impressed, as with Dolinger, with the flow of logic: there was substance, and I felt good about listening to this possibly insane man bark his carefully considered rant from a balcony. Orcbrand stepped away, and soon the lights were out again: there was a stream of projected light from Haywire’s command center. On the windows and wall above the balcony, there were a series of paintings, which will comprise the winter collection at the National Futurist Gallery.Here are a few samples.

I was withholding judgement on the art at the time: it was hard to see clearly that night. But, looking at these paintings now, I am frankly a little worried. What I see are simple, low-resolution figures or a landscape painted by rightwing posters in good standing. The market dynamics in commercial arts are well known: artists with established followings naturally draw more attention and higher prices–and a gallerist attempting to remain in business must be attentive to economic reality. Further, I’m sure that sourcing art for a controversial, niche gallery like this is difficult. Still, a critic like me wonders if this gallery will be a space for works chosen chiefly with an eye to follower-count on X or instagram or TikTok. Instead, I’d like to see arresting works of art, which demand discipline; I’d like to see work I can describe with a combination of at least two of the following descriptors: (a.) ultra-high definition, (b.) expressive color, and (c.) large size; I’d like to see video installations with high-effort film projects and animation. In short, I’d like to see art that clearly required a lot of time and attention to execute. What I see above frankly does not strike me as oriented to the future.

One of the worries I have about art oriented towards a shared-values scene is that for a lot of people, simply seeing their values reflected in a piece of art is good enough. Wendell Berry, I think, is a good example of this phenomenon: I have never read a Wendell Berry poem that I thought was particularly powerful. Still, he appeals to people like me, and I’m often seeing those who share my values praising him and his work. I want to encourage our artists to transcend this kind of scene parochialism, and the way through is laser focus on quality.

At some point, enough attendees had arrived that a number of us helped set up more folding chairs on the floor in front of the wooden platform; again, I was happy to see people arriving and participating in this event. By the end of the night, there were probably more than 30 people present.

Soon, Alexander Adams appeared in a Zoom meeting window displayed across the walls and stained glass windows. To his credit, Adams also spoke powerfully about the future of art and his own place in it. His personality seemed more intense than Gio’s, more explicitly right wing. I found this to be normal and relaxing; I liked the idea of sitting in a church listening to him talk about art: I liked the aura, basically.

When Adams was finished, there was a kind of break: the room was suddenly lit, and Haywire directed the group to enter another room, where there would be food and drinks and piano, and we did so, filing into a dining room area with a long table. There was crudité and wine and other food, but the real point of interest in a room like this, for me, was the other people. I’ve found that in any of the events that I’ve been to–the Mars Review White Party, any number of events at Sov House, The New Criterion, the Brooklyn Center for Theatre Research–the other attendees have been approachable and smart and nice. In my life, I’ve seen a number of scenes: arts scenes, political scenes, scenes associated with city clubs, and so on. So far, the crowd roughly associated with downtown/Dimes Square, the young people in the NYC area weary of the gladiatorial leftwing scrupulosity, have been among the most agreeable. I began introducing myself and chatting with others, and within minutes, I was engaged by two guys about my age (39) or older, asking about the poptimism question I posed during Gio’s Zoom session. Both of these guys–Leo and Aaron–were cool and smart, and I felt I was learning from each of them. We probably talked for something like 30 minutes, I would estimate, mostly about books, examples of good work happening within universities, varieties of feminism, and so on. It was refreshing and probably my favorite part of the night. We drifted apart, talking to others, and returned to our previous conversation if we ran into each other again. All the while, The Pianist, a poster I’ve subsequently chatted with on X and found to be similarly smart and cool and open, played piano in a style Haywire described as “Futurist Classical Baroque.” What I heard of the performance sounded furious and dissonant, but I did not hear very much of it because I was absorbed by various conversations.

Soon, I understood that most people had returned to the main event space and that there were more manifestos. I listened to another manifesto, whose content I no longer remember and then returned to the dining room, where I ended up in conversation with a number of people about legitimate and illegitimate episodes of #metoo cancellation and problems with online racism. This group was fun and funny, but I don’t really remember exactly who everyone was. At this point, it was getting close to 11:00, and I decided I had to leave–I had to go back to Connecticut for work the next day. Still, the night apparently went on quite late in my absence: Haywire danced again; there was manifesto reading, and another projected Zoom meeting, this time with Peter Clarke of the Team Futurism podcast. He read a Dadaist manifesto, which was interrupted by connectivity problems, and then a number of the attendees went to an after-hours bar.

I enjoyed this event very much, and I have high hopes for this gallery. While there are overt fascist concepts at play, I don’t actually think there is legitimate Fascism at the heart of this project: I don’t think American Nationalism is the inspiration. I do think, though, that the political foundation of mainstream art, which has been shaped by both materialist Liberalism and Leftism, is what a number of people, both at this party and elsewhere, do reject. The impulse towards fascist ideas is, yes, a contrarian impulse towards a counterbalance against cultural marxism, but it is also an impulse towards art imbued with immaterial aura and values. I happen to think that the fascist/romantic embrace of man’s animal nature is ultimately a kind of misunderstanding: I believe that we should be striving to transcend our bestial natures, guided by careful consideration of our consciences. Still, I appreciate the right for its defense of immaterial reality in the face of Marxist and Liberal materialism. While the conception of man as a tribal, warlike animal, who worships animals and earth-bound spirits, strikes me as primitive, the vision of man as a kind of soulless intellect optimizing for this or that economic output strikes me as hardly different from OpenAi’s view of their ChatGPT product line.

So glad you could make it! Love your commentary and criticism. Thank you for stopping by and sharing your thoughts on this. Hoping to see you at our official opening in March.

This can be only to the good but I can't say I liked featured art much

There is much work to be done!